Mike Coburn Soldier Five Pdf Merge

SOLDIER FIVE is an elite soldier's memoir of his time within the Special Air Service (SAS) and, in particular, his experiences during the Gulf War. As a member of the Special Forces patrol now famously known by its call sign Bravo Two Zero, he and seven others were inserted hundreds of kilometres behind enemy lines. Their mission was to reconnoitre targets, undertake surveillance of Scud missile sites and sabotage Iraqi communications links, but was to end in desperate failure.From the outset the patrol was dogged by problems that contributed both directly and indirectly to the demise of the mission. The patrol's compromise, and subsequent attempts to evade Iraqui troops, resulted in four members of Bravo Two Zero being captured and a further three killed. But the story goes further than the Gulf War itself. Despite numerous books, films and articles on the same subject, the British Government has done its utmost to thwart the release of Soldier Five, at one stage claiming the book in its entirety was confidential. A campaign of harassment that took some four-and-a-half years of litigation to resolve has now resulted in this explosive publication.

SOLDIER FIVE is a gripping and suspenseful account of one man's experiences as a Special Forces soldier. Revealing his conflicts, loyalties and relationships forged, it is the resolution of a soldier's determined fight to see his story told.

SAS Gulf War patrolBravo Two Zero was the of an eight-man (SAS) patrol, deployed into during the in January 1991. According to 's account, the patrol was given the task of gathering intelligence, finding a good lying-up position (LUP) and setting up an (OP): 15 on the Iraqi (MSR) between and North-Western Iraq; however, according to 's account, the task was to find and destroy Iraqi missile launchers along a 250 km (160 mi) stretch of the MSR.: 35The patrol has been the subject of several books. Accounts in the first two books, one in 1993 by patrol commander Steven Mitchell (writing under the pseudonym ), and the other in 1995 by Colin Armstrong (writing under the pseudonym Chris Ryan), do not always correspond with one another about the events.

Both accounts also conflict with SAS's (RSM) at the time of the patrol, in his 2000 memoir, Eye of the Storm. Another book by a member of the patrol, Mike Coburn, entitled, was published in 2004., a former soldier with the SAS, went to Iraq and traced in person the route of the patrol and interviewed local Iraqi witnesses to its actions; afterward, he alleged that much of Mitchell's Bravo Two Zero and Armstrong's The One That Got Away were fabrication. His findings were published in a British television documentary filmed by, and in a 2002 book entitled The Real Bravo Two Zero. Both Armstrong and Mitchell reacted angrily to the documentary and Asher's conclusions.Mitchell was awarded the for his actions during the mission, whilst Armstrong and two other patrol members (Steven Lane and Robert Consiglio), were awarded the. Bravo Two Zero patrol members.

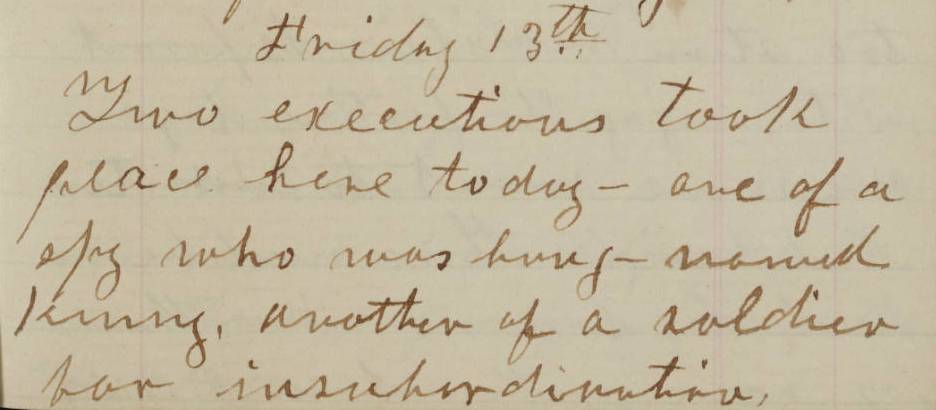

From left to right: Ryan, Consiglio, MacGown (obscured), Lane, Coburn (obscured), Mitchell (obscured), Phillips, Pring (obscured)., patrol commander: 1 former.: 21 Captured by the enemy, later released. Author of and referred to as 'Andy McNab' in the books.

Vincent David Phillips,: 208 patrol: 3 former.: 30 Died of during action, 25 January 1991.: 213 Colin Armstrong,: 19 former 23(R) SAS. The only member of the patrol to escape capture.

Author of and better known under his pseudonym as '.: 22 Ian Robert 'Dinger' Pring former. Captured by the enemy, later released. Robert Gaspare Consiglioformer 42 Cdo RM.: 32: 19 Killed in action, 27 January 1991.: 172 Steven John 'Legs' Laneformer of, and former Parachute Regiment.: 19 Died of during action, 27 January 1991.: 226 Malcolm Graham MacGown, former. Captured by the enemy, later released. Referred to as 'Stan' in the books. Mike 'Kiwi' Coburn (pseudonym) former. Captured by the enemy, later released.

Referred to as 'Mark the Kiwi' in the books. The patrol Background In January 1991, during the prelude to the, were stationed at a in.

The squadron provided a number of long-range, similarly tasked teams deep into Iraq including three eight-man patrols: 'Bravo One Zero', 'Bravo Two Zero' and 'Bravo Three Zero'.: 16 Asher lists one of the three patrols as 'Bravo One Niner',: 37 though it is not clear whether this is one of the same three listed by Ryan.Insertion On the night of 22/23 January, the were transported into Iraqi airspace by a helicopter, along with Bravo Three Zero and their vehicles.: 39 Unlike Bravo Three Zero, the patrol had decided not to take vehicles. According to McNab's account, the patrol walked 20 km (12 mi): 55 during the first night to the proposed location of the observation post. However, both Ryan's and Coburn's accounts put the distance at 2 km (1.2 mi). Eyewitness accounts of and Asher's re-creation support the Ryan/Coburn estimate of 2 km (1.2 mi). Ryan states the patrol was intentionally dropped only 2 km (1.2 mi) from the observation post because of heavy pack weights.: 29According to both Ryan and McNab, the weight of their equipment required the patrol to 'shuttle' the equipment to the observation post.: 95 Four members would walk approximately 300 m, then drop their and wait. The next four would move up and drop their Bergens, then the first four would return for their jerry cans of water and bring them back to the group, followed by the second four doing the same.: 42 In this manner, each member of the patrol covered three times the distance from the drop off to the observation post.Soon after the patrol landed on Iraqi soil, Lane discovered that they had communication problems and could not receive messages on the patrol's radio. McNab later claimed that the patrol had been issued incorrect radio frequencies;: 393 however, a 2002 report discovered that there was no error with the frequencies because the patrol's transmissions had been noted in the SAS daily record log.

Lays the blame for the faulty radios on McNab as the patrol commander; it was his job to make sure the patrol's equipment was working. Compromise In late afternoon of 24 January, the patrol was discovered by a herd of sheep and a young shepherd. Believing themselves compromised, the patrol decided to withdraw, leaving behind excess equipment.

As they were preparing to leave, they heard what they thought to be a tank approaching their position. The patrol took up defensive positions, prepared their, and waited for it to come into sight. However, the vehicle turned out to be a, which reversed rapidly after seeing the patrol. Realising that they had now definitely been compromised, the patrol withdrew from their position. Shortly afterwards, as they were exfiltrating (according to McNab's account), a firefight with Iraqi and soldiers began.In 2001, interviewed the family that discovered the patrol. The family stated the patrol had been spotted by the driver of the bulldozer, not the young shepherd.

According to the family, they were not sure who the men were and followed them a short distance, eventually firing several warning shots, whereupon the patrol returned fire and moved away. Asher's investigation into the events, the terrain, and position of the Iraqi Army did not support McNab's version of events, and excludes an attack by Iraqi soldiers and armoured personnel carriers. Coburn's version, partially supports McNab's version of events (specifically the presence of one ) and describes being fired upon by a 12.7 mm heavy machine gun and numerous Iraqi soldiers. In Ryan's version, 'MacGown also saw an armoured car carrying a machine gun pull up. Somehow, I never saw that.' : 53 Ryan later estimated that he fired 70 rounds during the incident.Emergency pickup British (SOP) states that in the case of an emergency or no radio contact, a patrol should return to their original infiltration point, where a helicopter will land briefly every 24 hours.

This plan was complicated by the incorrect location of the initial landing site; the patrol reached the designated emergency pickup point, but the helicopter never appeared. Later revealed that this was due to an illness suffered by the pilot while en route, necessitating his abandoning his mission on this occasion.Because of a malfunctioning emergency radio that allowed them only to send messages and not receive them, the patrol did not realise that while trying to reach overhead allied jets, they had in fact been heard by a US jet pilot. The jet pilots were aware of the patrol's problems but were unable to raise them.

Many were flown to the team's last known position and their expected exfiltration route in an attempt to locate them and to hinder attempts by Iraqi troops trying to capture them.Exfiltration route Standard operating procedure mandates that before an infiltration of any team behind enemy lines, an exfiltration route should be planned so that members of the patrol know where to go if they get separated or something goes wrong. The plans of the patrol indicated a southern exfiltration route towards. According to the SAS daily record log kept during that time, a transmission from the patrol was received on 24 January. The log read 'Bravo Two Zero made TACBE contact again, it was reasonable to assume that they were moving south', though in fact the patrol headed north-west towards the border. Coburn's account suggests that during the planning phase of the mission, Syria had been the agreed-upon destination should an escape plan need to be implemented. He also suggests that this was on the advice of the officer commanding B Squadron at that time.According to Ratcliffe, the change in plan nullified all efforts over the following days by allied forces to locate and rescue the team. McNab has been criticised for refusing advice from superiors to include vehicles in the mission (to be left at an emergency pickup point) which would have facilitated an easier exfiltration.

Another SAS team used in this role when they also had to abandon a similar mission. However, it is also suggested that the patrol jointly agreed not to take vehicles because they felt they were too few in number and the vehicles too small (only short-wheelbase Land Rovers were available) to be of use and were ill-suited to a mission that was intended to be conducted from a fixed observation post. Separation During the night of 24/25 January,: 118 while McNab was trying to contact a passing aircraft using a communicator, the patrol inadvertently became separated into two groups. 66 mm rocket launcherEach member of the patrol wore a uniform with a era sand-coloured desert smock.: 37 While the other members had regular issue army boots, Ryan (the only member to avoid eventual capture) wore a pair of £100 'brown -lined walking boots.' : 38Each member carried a, one sandbag of food, one sandbag containing two, extra ammunition bandoliers and a 5 imp gal (23 l) jerry can of water.: 29: 66 'The belt kit contained ammunition, water, food and trauma-care equipment.' .

^ Ryan, Chris (1995). The One That Got Away. London: Century.

^ McNab, Andy (1993). Great Britain: Bantom Press. 'Battle of SAS Gulf Patrol gets bloody', 'The Guardian', 26 May 2002.

14 December 1998. P. 13620. ^, The London Gazette (Supplement), Gazettes online (54393), p. 6549, 9 May 1996, retrieved 25 October 2011. ^ Asher, Michael (2003).

England: Cassell. ^ Coburn, Mike (2004). Soldier Five. Great Britain: Mainstream Publishing.

Lowry, Richard S (2003). The Gulf War Chronicles. P. 27. ^ Cowell, Alan (5 March 1991). The New York Times. Retrieved 25 October 2011. (PDF).

Soldier Five Mike Coburn

Retrieved 25 October 2011. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

^ (PDF). Archived from (PDF) on 7 October 2011.

Retrieved 25 October 2011. ^ Moss, Stephen (12 March 2004). The Guardian. Retrieved 25 October 2011. ^. The New Zealand Herald. 19 December 2006.

Maguire, Kevin. Retrieved 25 October 2011. ^ Taylor, Peter (10 February 2002).

Retrieved 25 October 2011. The Independent. 7 December 2000. Archived from on 4 July 2009.

Retrieved 25 October 2011. The New Zealand Herald. 20 March 2003. Fowler, Will (2005). SAS Behind Enemy Lines: Covert Operations 1941-2005.

London: Collins.